Stars and a Siberian Forest. Anne-Cécile Vandalem’s »Kingdom«

by Joseph Pearson

08. April 2022

In 2019, the Belgian theatre-maker Anne-Cécile Vandalem told me, »We are so tied to reality and, for me, theatre and poetry are forms that allow us to see from a different point of view. It’s said that if you look at a star in the sky straight on, you have trouble seeing it. It’s only when you look a little bit to one side that you see it better. For me, this explains my approach to theatre.«

A trilogy of such fictions––the three sister stars of Orion’s belt?––will be completed by »Kingdom«, premiering at the Schaubühne’s FIND 2022 festival this weekend. The previous instalments, »Tristesses« and »ARCTIQUE« showed at FIND in 2017 and 2019 respectively. I appreciate Vandalem’s star metaphor because it gives a sense of the great spaces that attract the director. It also suggests her reflections on failure, the impossibility of touching the ideal. I ask her about the relationship between »Kingdom« and the preceding plays.

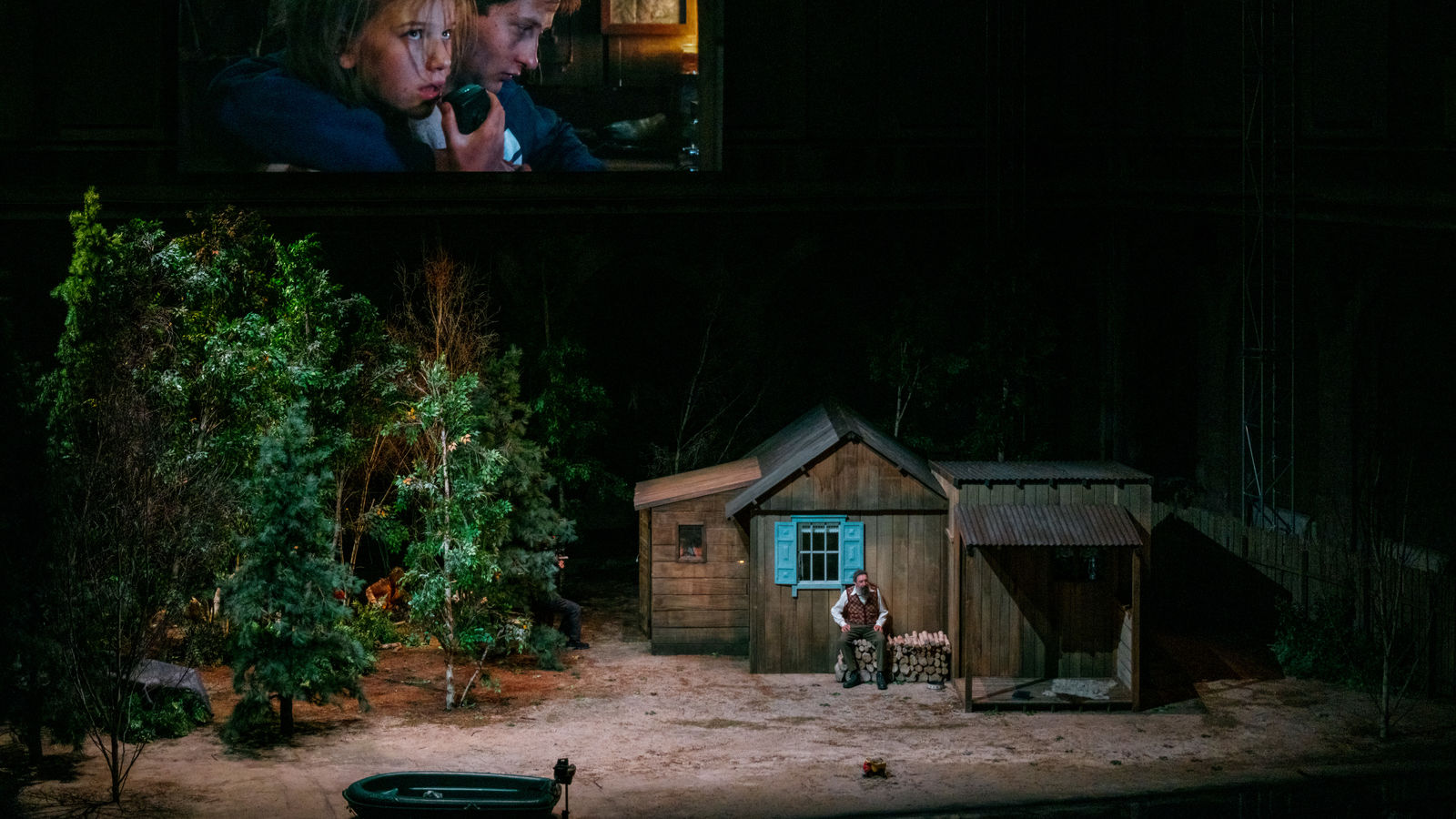

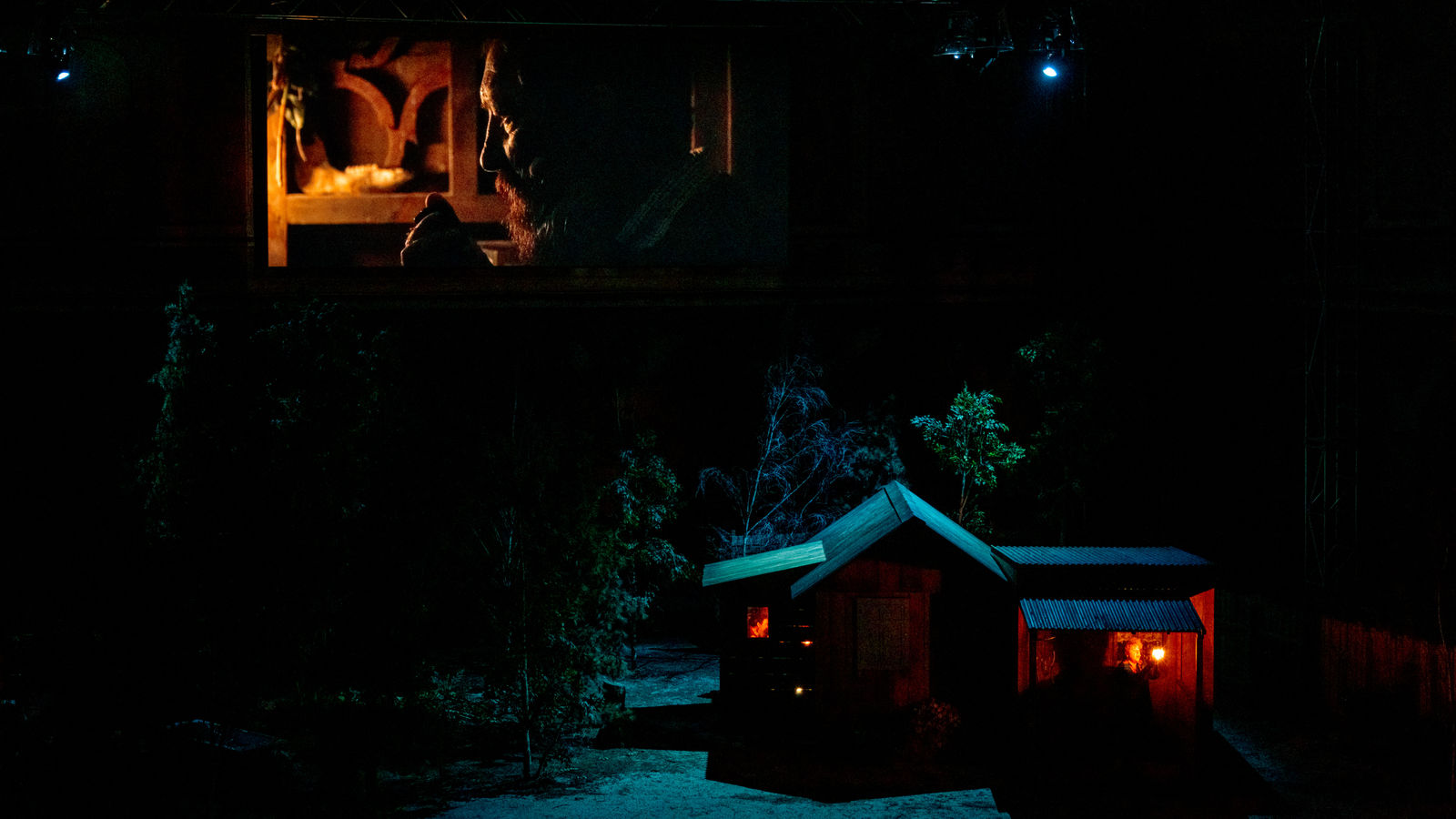

Vandalem explains, »I work in cycles. I like the possibility of multiple stories that interweave my intuitions and preoccupations. It is also a search for devices that allow us to reveal more. In this cycle, I wanted to reflect on humanity’s failures––political in »Tristesses«, ecological in »ARCTIQUE«, although both subjects are imbricated. In »Kingdom«, I wanted to consider what failure means for the future, for those who will exist in an ever more perilous and uncertain future. I thought of the device of focusing on encounters with children: how do they see their futures, as opposed to me, an adult. It was at this point in the project that I came across the work of Clément Cogitore, when his study of families living in the Siberian Taiga was still in exhibition form, rather than a film.«

Clément Cogitore is a French filmmaker and installation artist. His 2017 documentary film, »Braguino«, about a remote community in the Siberian wilderness, is an atmospheric journey that began with research into the Old Believers, or those practising Orthodox rituals dating before 17th-century reforms. After meeting Sasha Braguine, who brought his family to the Taiga in search of a utopian existence, Cogitore returned with a cameraperson two years later to document the family’s lives. The result is a poetic, open-ended work: helicopters move in and out of cloud; bears are hunted and dismembered; the children of the family play on an island that protects them from wild animals. But the Braguines are not alone. Another family, the Kilines, have also planted their flag in this remote locale, engaging the Braguines in a bitter rivalry. The Braguine children play at a wary distance from the Kiline brood––separate childhoods, with taught resentment of the only other beings their age.

Vandalem tells me that Cogitore’s art intrigued her precisely because it did not answer so many questions, »In Cogitore’s work, the children are not given much opportunity to speak, particularly in the exhibition. I wrote to him, he met me, and I said I would like to make a work based on his work. I made it clear that I would not be adapting »Braguino« to the stage––that would not be interesting––but rather creating a fiction that answers the questions that the film posed for me. And he accepted.«

»Is it that your work is fiction which distinguishes it from Cogitore’s?«

»One cannot say that »Braguino« is strictly non-fiction and documentary, and my story fiction. His is, of course, an artist’s film, a poetic point of view, and it only tells one part of the »Braguino« story. My theatre, however, does not just change the material, such as the characters, but also re-interprets it. For example, I took this film to different places, to publics from rural communities and little towns with limited access to technology and »high culture«, and they were shocked by the documentary, and what they perceived as the egotism of Braguino in exposing his family to the life they ended up living. It is a form of Occidentalism to think of Braguino’s world as a utopia––this return to nature, to virgin territory. I wanted to revisit the Braguino story through mistakes and failures rather than through utopias. This is possible through fiction in way that it is not through the documentary film.«

Certainly, Vandalem’s observations resonate with my reactions to »Braguino«, in which the artist’s helicopter descends, the camera staring down his anthropological subjects. Looking more closely, the lives in this wilderness are impoverished and the conflicts seem petty. It is a view that invites revision, which »Kingdom« offers. In Vandalem’s work, there is a habitual tension between the myth of a promised land––she’s done her tour of Nordic landscapes from a Danish island to the frozen ocean off Greenland to the Siberia Taiga––and the horror behind the promise. As she tells me, »There is a contradiction of the imagination of these spaces and the ecological and political realities, which are terrible.«

I ask, »Instead of Old Believers, you set your remote community among animists. Could you tell me how important the animal world is to your art? I can’t help but think of the sudden appearance of a polar bear on the cruise liner in »ARCTIQUE«.«

She replies, »In »Kingdom«, the whole ensemble of living things is important, even plants. The question of animism runs through the piece. In this play, there’s no bear but there are dogs, real ones. When I started to write, I knew they would be there, even before I saw »Braguino«. The animals would tell the story along with us. The rehearsals would be conditioned by animals, the actors would be influenced by the presence, as they would be by the presence of children on set. They oblige us to position ourselves differently in the space. I realised the limitations of working with props in »ARCTIQUE«, with the polar bear. We worked with him but he didn’t work on us. He was hard to make exist, not like real three dogs.«

»I have heard that the forest also has a role. It makes music––«

»Unlike »ARCTIQUE« where we had a band on board the ship, here we have a family that accompanies all their daily steps with songs. They sing at work, about love, for the loss of a family member. No matter what happens, song is present. All the instruments are made from natural materials––wood, stone, horn, fibres, rocks––and the players are difficult to see behind a forest. The music is live but we might not immediately remark on it.«

»Let’s return to the children«, I suggest, to conclude, »In »Braguino«, Cogitore is filming their everyday lives. As documentary subjects, they are unlikely to be making an abstraction of their roles. How do you work with children on stage?«

»When working with them«, the director replies, »It is difficult to make them believe in the fiction. They always know they are playing. We can tell children to imagine they are thieves, but they know they are not. Their relation to belief in the creation of something is difficult; you need to give them concrete examples: imagine someone taking away your house, your parents. But the children are self-protective; they tend to laugh in response. It helped that we worked with them for a long period: one and a half years before the premiere. I wanted them to grow with the story over a long period, and not just experience it for eight weeks. I wanted them to incarnate their characters slowly. It was only this way that they would begin to believe in their world.«

Kingdom

(Brüssel)

von Anne-Cécile Vandalem / DAS FRÄULEIN (KOMPANIE)

Frei nach Braguino von Clément Cogitore

Letzter Teil der Trilogie »Tristesses, Arctique, Kingdom«,

erschienen bei Actes-Sud Papiers

Regie: Anne-Cécile Vandalem

Saal B

Premiere war am 09. April 2022

Pearson’s Preview

Archiv

April 2016

FIND 2016 »Hearing« between the lines

April 2016

FIND 2016 The Voice of the Leader: A Study Part Two of a Conversation with Sanja Mitrović

Februar 2016

Borgens Vorhang lüften

| Seite 7 von 10 Seiten |