»Beware of Pity«: Playing Ball with Simon McBurney

by Joseph Pearson

30 November 2015

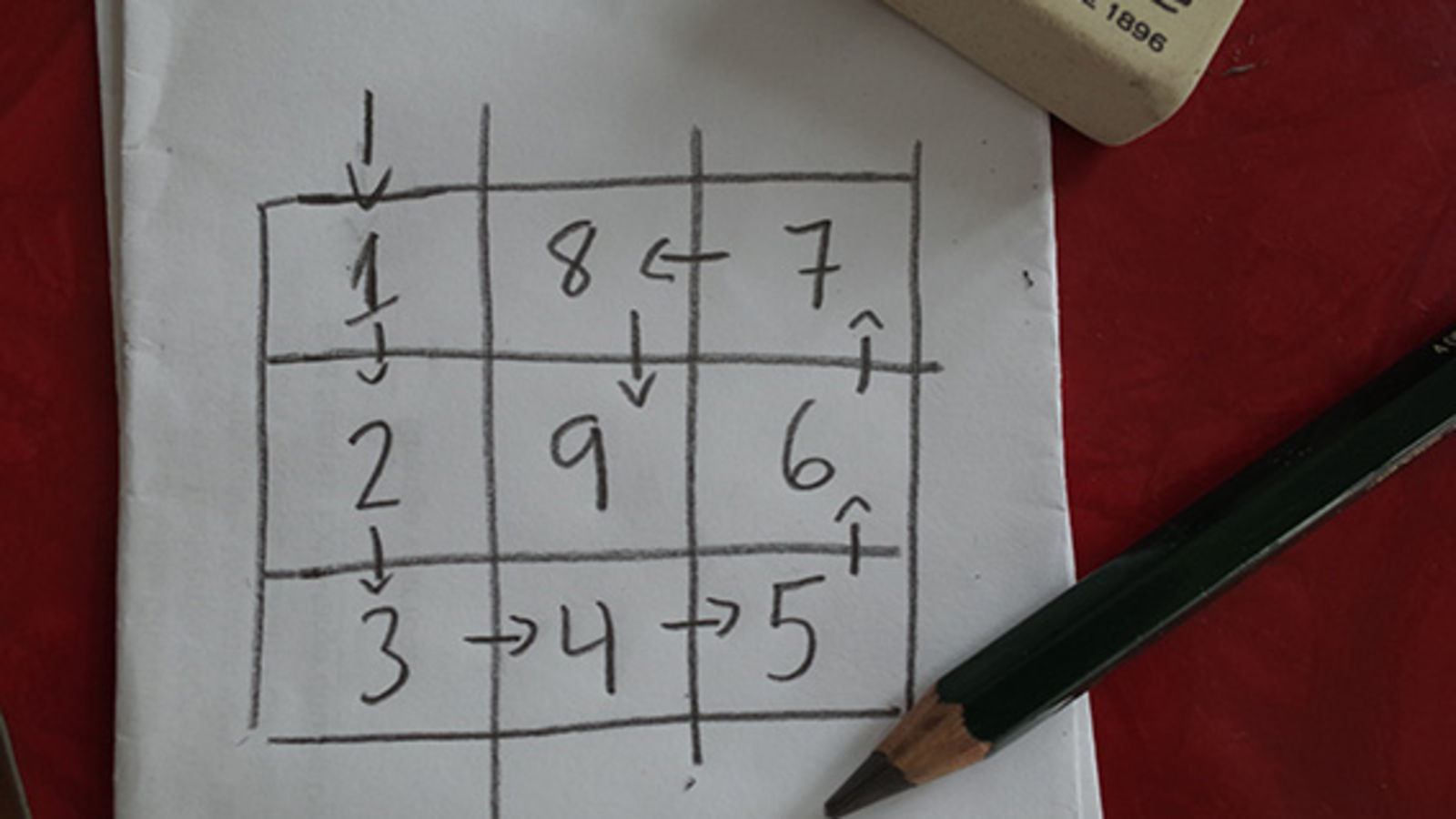

How to Play Nine Square

Let me introduce you to a game that tells you something about the production »Beware of Pity«. Yes, you! Come up on stage! I don’t want you lurking in the wings. The actors are already busy playing »Nine Square« before rehearsal begins. A large 3x3 grid is taped to the ground. You bounce the ball about its nine squares. If your neighbour misses, she is banished from the grid. You progress through the vacated squares, around the edge to the middle. If you reach the goal, you will be King!

Let’s see how good you are at the game. Bounce the ball into actor Robert Beyer’s square. He responds by shooting it into Laurenz Laufenberg’s, who reflects it to the dramaturge, Maja Zade. She delicately tips the ball into square 5, where Eva Meckbach dives and misses. She’s out! Eva steps out of the grid and joins the line forming before Square 1, where the tech crew have arrived. The other actors – Johannes Flaschberger, Moritz Gottwald – advance one step forward. The Queen, Marie Burchard, has the honour of starting the game again. But she misses. With a theatrical shout, she steps down from her throne of glory. Christoph Gawenda, with a mock bow, advances from square 8 to take her place. King, but only for a minute.

Zweig’s Novel

What the Schaubühne actors call »Nine Square« was invented by Complicite, the British theatre group. Its founder, Simon McBurney – the UK’s leading director on the festival circuit – is in Berlin to direct the novel by Stefan Zweig. »Beware of Pity« tells the story of a young officer’s disastrous struggle with his sense of honour. Out of pity, he is unable to break off a courtship with a wealthy, lame girl who falls in love with him.

»You have a very simple juxtaposition between a man who is emotionally completely inarticulate, emotionally immature. It’s almost a perfect fit, because you have a young girl who is physically disabled but emotionally completely articulate… He learns to empathise with her through a series of terrible errors«, McBurney recounts.

The protagonists’ relationship becomes the ne plus-ultra of destructive ›Helfersyndrom‹ (Helpers-syndrome). The 1939 novel has recently been rediscovered by the English-speaking world, thanks to a lucid new translation by Anthea Bell published by Pushkin Press, and the Zweig-esque film by Wes Anderson, Grand Budapest Hotel.

The story is told by a narrator immediately before the Second World War. It looks back to the verge of the previous disaster, the First World War. Speaking of the vanished Austro-Hungarian Empire, McBurney tells me: »Edith is that world, and she will be destroyed. And I think we are on the verge of another disaster… that for me is the premise«.

Nine Square and Making Mistakes

I first saw director McBurney’s work (his piece »Mnemonic«) in New York, in 2000. McBurney trained with the l’École Jacques Lecoq, in Paris and he has subsequently developed many of its techniques. I was impressed back then by the way movement and space took priority, how the notion of character was fluid, how actors exchanged roles. In one scene, each member of the company took turns being a 5300 year-old ice man exhibited on a slab.

Complicite’s highly addictive ball game might help us understand McBurney’s »Beware of Pity« and its concerns with movement, space and collaboration. On the surface, the game simply warms up the company. It trains precision, gets the actors’ minds moving along with their bodies. The childlike tone of play lightens the mood.

But Nine Square is also a game that allows you to make mistakes: the rules are flexible. If you miss the ball, don’t be surprised when the others cry: »second chance!« to prevent your elimination. In the same vein, McBurney is willing to try again. He often begins directing a scene with the phrase, »This might not work. But can I see what happens if…«

In the rehearsal I attend, they work on a scene where the Baron’s lame daughter, Edith von Kekesfalva, tries to walk. The young officer Anton Hofmiller reacts in an unexpected way.

McBurney suggests, »Let’s try having everyone but Edith walk, what would that look like?« The experiment yields results. »Now, let’s see if it looks different in period costume«, he tries. Other possibilities are explored: What happens if one actor sits at a different table than the others? Or if her voice is modified? Or if you take over the other actor’s lines half-way through? »Now throw down the scripts, improvise! Come on, this is not naturalism, it’s like opera, bring up the emotion!« There’s no fear in a big mess, or even in having to throw out a whole day’s work. I am reminded of a chemist combining elements to explore the possibilities, and ready to go forward without fearing trial and error. It’s all about second chances, just as in Nine Square.

He explains, »Every time I take on a piece I am trying to engage with something new, trying to understand the piece itself. I don’t really know what I’m looking for. But if I knew what I was looking for, there would be no point in looking. Like an archaeologist, you are not going to bury one of the Pharaoh’s tombs, and then dig it up and say: I found the Pharaoh’s tomb! What you do is go and dig and hope to find it. Sometimes you don’t«.

The Unity of the Ensemble

The ball game is also useful preparation for balancing different acting styles and personalities in the rehearsal space. Differing levels of assertiveness become immediately apparent during the game. While some are intent on winning, others think the goal is silly. Everyone is familiarised with the testosterone levels in the room, or with each other’s moods, just by the way one hits the ball. Meanwhile, no one occupies the same space in the grid for very long. Everyone eventually becomes King, the way that in »Mnemonic« everyone became the iceman on the slab. This creates unity in the troop.

In the early rehearsals of »Beware of Pity«, the roles are not yet fixed. McBurney has them share the parts: actors try out all the different characters, they pass the lines between one another. There is the risk that the actors – naturally interested in who is going »to be« Anton or Edith – are pitched into competition. But Nine Square already helps equalise moods, make accommodations; it might even defuse rivalries.

The actors also have a common identity defined by the story, which is the retrospective narration of an older Hofmiller on his youthful mistakes. McBurney says, »For me, all the characters are part of Hofmiller’s imagination, through whose voice the story is being told in any case. Because the story is within his head, the idea underneath it is the question of consciousness«. McBurney continues that there is a problem with expectations if one wants traditional characters, »It’s not a play. You have to be very careful. Everyone is within the aegis of Hofmiller«.

Telling a Story, Also with Sound

The fact that Nine Square happens right on stage, where minutes later the actors are rehearsing, gives a spatial coherence between the game and stage design. The actors sit at the minimal set of a long table, which is not much more elaborate than Nine Square’s lines on the ground.

Here, the team make modifications to the script, so that by the end it becomes a quasi-devised piece. The rehearsal is very text-based, upending Complicite’s reputation for being more concerned with movement than text, or for having an aversion to linear stories. McBurney claims not to speak German, but he reads the script rather well on stage. A translator nonetheless hovers like an angel in the background behind the actors.

McBurney tells me, »I’m interested in this idea of just telling a story. I think it has a lot to do with the fact that I tell stories to my children at the moment. And I think people enjoy having a story told to them. Within the theatre it’s interesting when people just say: ›this happened, and then this happened‹ and then you begin to act it out in some way«.

The concern for storytelling is accompanied by attention to how the text sounds. Nine Square is not really a sound game. Or is it not revealing that I have not focused on the sounds of Nine Square – the shuffling of feet, the yelps of victory or disappointment, the thud of the ball between the lines – which make for an emotional sonic backdrop? Have not all these communicated something more directly than words? Have they also not told a story?

One might consider too the similarities between the way movement and sound operate for the director. His production »Amazon Beaming«, in workshop form, was shown at last year’s F.I.N.D. festival at the Schaubühne. Every audience member was given earphones that manipulated the location of sound (left, right, above, coming straight at you…), to suggest movement on stage.

One of most charming aspects of a McBurney rehearsal is the way he actually conducts his actors, like a maestro. As the actors read the script, his hands are raised. He indicates when they should pass on the lines of a character to someone else, when they should improvise. He indicates rhythm, dynamics, crescendos, pauses, beats, even tone. Then an actor is instructed to use a looper. »Add some reverb to that«, McBurney instructs the sound designers. Working as if on a concert, they mix the repeated words »immer, immer, immer« (»forever…«) shaped by background music and samples. The score has a grand shape. That and the changing material, is, in musical terms, a little more Mahlerian than say a Mozart sonata-allegro form.

Articulating the Emotion: Pity

Sound has the advantage of not being limited by language, it sets one free from a particular denotation, and this is useful in a piece whose concern is how an emotionally undeveloped young man, who cannot articulate emotions, can communicate with a disabled woman who is talented with language.

As Simon McBurney explains, »The question is: what is music and what does it do? I think there is plenty of evidence to suggest that music came before words. It can communicate certain things in a way that is more direct than words. It is constantly appealing to something that is primordial for us«.

»A sound is going to give you a very direct emotional communication, which a word by its construction attempts to separate from the world. It is the same way a story, a fiction, is not the world. We as human beings, as a consequence of our language, get confused as to the nature of reality because of the words which we use. All these things are in fact fictions which are created and are things which separate us from the real issue«.

»In a way, that is a question here. It’s called Beware of Pity, but the whole question is the articulation of the emotion. How is it articulated? It isn’t articulated by form; it is by something else«.

Beware of Pity

by Stefan Zweig

In a version by Simon McBurney, James Yeatman, Maja Zade and the ensemble

Director: Simon McBurney

Premiered on 22 December 2015

Mit dem Aufruf des Videos erklären Sie sich einverstanden, dass Ihre Daten an YouTube übermittelt werden. Mehr dazu finden Sie in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

Bei Klick auf die Schaltfläche "Akzeptieren" wird ein Cookie auf Ihrem Computer abgelegt, so dass Sie für die Dauer einer Stunde, diese Meldung nicht mehr angezeigt bekommen.

Pearson’s Preview

Archive

April 2024

Icy Myths in the Russian East

The Exiles of KnAM’s »My Little Antarctica« at the Schaubühne

April 2023

FIND 2023

Nostalgic, Not Sentimental

The Wooster Group as »Artist in Focus« at the Schaubühne

| Page 1 of 10 pages |