Icy Myths in the Russian East

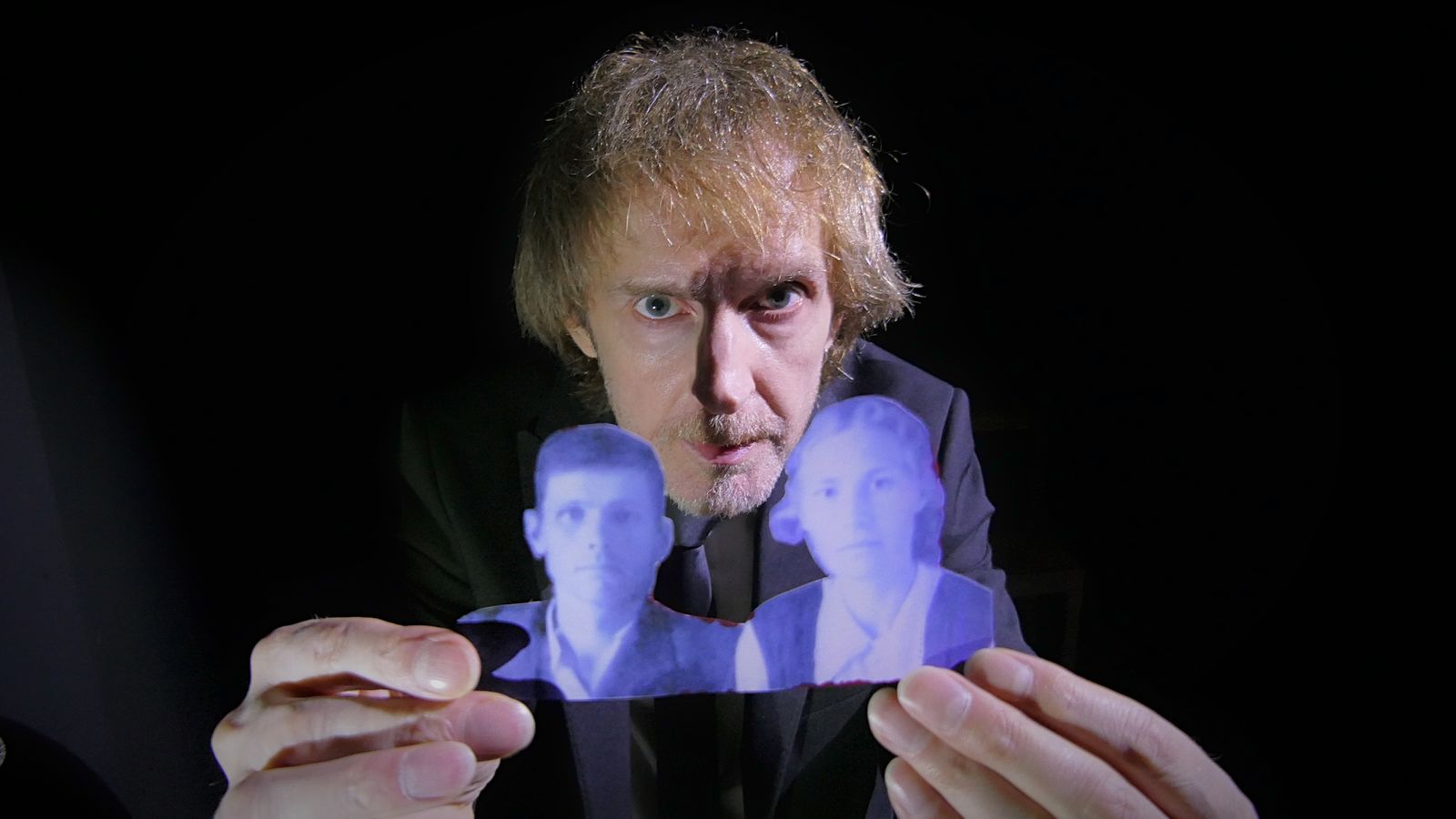

The Exiles of KnAM’s »My Little Antarctica« at the Schaubühne

by Joseph Pearson

24 April 2024

What do you know about the far eastern reaches of Russia? Perhaps you are one of those intrepid travellers who has taken the trans-Siberian to that distant edge. Or one of the rare few who have ferried from Japan to Vladivostok over the glassy North Pacific. Or you might have made a less arduous journey in the comfort of an armchair, reading Anton Chekhov’s narrative of the prison colony of Sakhalin in 1890––a place he felt tested the limits of humanity. But for most living in Western Europe, these locations are the back of beyond, and susceptible to myth.

As Tatiana Frolova’s KnAM Theatre illuminates, communities in that icy geography, such as Komsomolsk-on-Amur, deep in Russia’s eastern Taiga, also tell legends about themselves. As the town’s name reflects, volunteers of the Communist youth organisation, the Komsomol, built the Stalinist buildings. However, the role of forced labourers from gulags is an inconvenient part of the Soviet story. Frovola’s piece, »Моя маленькая Антарктида« (»My Little Antarctica«), introduces a theatre company that has fled a part of Russia known for its prisoners and exiles, to go into political exile itself. Since the war in Ukraine, these vocal critics have based themselves in Lyon, France.

It’s the midpoint of the #FIND2024 festival at the Schaubühne, and I’m meeting Tatiana Frolova to talk about her work, which will premiere this week.

Joseph: Why did you choose to write about Komsomolsk-on-Amur?

Tatiana: I was born there. The whole team and their families born there too––generations from the 1960s to the 1990s. We started our theatre in 1985, in the USSR. It was the time of Gorbachev––the wave of changes accompanying Perestroika, and we followed that wave. And in almost every play we do, we speak about this place. The people who live there don’t know about the Gulag history of where they are from, so it’s important for us to tell this story.

Joseph: How important is the cold in your production? And why do you name your play after Antarctica?

Tatiana: Eight months of the year there it is cold, and every aspect of life was cold! It is even painful––it can be -45 C––to go from home to the theatre. It is the core of how we lived there: the frozen heart. This means there are no emotions: people turn off their emotions to survive.

Joseph: The cold is not just about the weather––

Tatiana: No, and we needed to survive it. That life was so difficult is something I’ve discussed in previous plays, such as the story of my grandmother, who battled with hunger. There was so little food that five of eleven children died; she couldn’t survive in this terrifying situation, so she turned off her feelings. Only in this way could she survive not just the physical cold, but the sad, societal situation. When she lost her children, she didn’t allow herself to cry because she needed to continue to live––she needed to survive.

Joseph: The city was built with forced labour from the Gulag. Tell me about this history.

Tatiana: The authorities created a myth: that the Komsomol came and built the city, but in fact most of the labour came from the Gulag. It was true that Komsomol came, but only about a hundred people, and in the first year they all died, from cold and hunger. They experienced terrible working conditions. They had no tools for their work, and in the play we explain how the workers’ hair froze to their cots. They basically lived outside, in makeshift buildings that were almost tents. We have a lot of photographic evidence of these conditions, but few want to confront this history, and instead, a beautiful story has replaced the reality. In our city, there were more than forty gulag encampments that provided forced labour consisting of political prisoners.

Joseph: With the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, did the legend change?

Tatiana: There was a short period when information about the past became available in the archive and museum, but then it was again made unavailable. Because the facts could not be remembered, the old legend was preserved.

Joseph: What is Russia’s interest in keeping this legend alive today?

Tatiana: Because the politics of Putin requires that people not know what happened: because this generation of politicians is descended from the grandparents involved. There is a genealogy of violence. Soviet secret services became the Russian ones we know today. Since 2001, more and more information has been hidden. Many people have been even arrested because they have tried to access the records. Yuri Dmitriyev is an example of someone who wanted to investigate the issues and was imprisoned, with others. And our whole theatre team was followed and threatened.

Joseph: At what moment did you decide to leave Russia?

Tatiana: When the war in Ukraine began in 2022, I decided there was no more hope. I had hoped that people wanted freedom, but the opposite was very much the case. Fellow Russians wanted war: I lost many friends for being against the war.

Joseph: Was it difficult to leave and go to France?

Tatiana: Our theatre company did it in two steps. At first, four of us went ahead. Then, the remaining three left. Many organisational aspects still needed to be taken care of in Russia, and these three were unsure whether the situation would deteriorate or improve. Because our city is so small, these three heard through their contacts that they would be the next to be arrested. Because it was possible they would land in prison, and because they could not live with the idea of not being able to make theatre in Komsomolsk, they also found their way out. We wanted to first go to Mongolia, because it would be easier from Eastern Russia, but the Corona virus epidemic complicated this, and the border was closed. And so, we went to Kyrgyzstan instead, where two theatres from France, one from Switzerland, and the »Sens Interdits« festival––who since 1999 knew our work––wanted to invite and support us.

Joseph: What is it like making theatre for new audiences now that you are based in France? Making theatre for people who know Eastern Russia is different than making it for those who have less awareness of the region––

Tatiana: Many people find similarities between our situation and their histories. Germans often say, after they have seen our productions, that they see a parallel with German history. Also, there is a relationship to what is happening today. Lenin and the USSR wanted to conquer the whole world. The same idea has a continuity with Putin and his conquests––his ideas for a Greater Russia.

Joseph: Here in the West, how afraid should we be of Putin?

Tatiana: We shouldn’t be afraid, but we should be awake.

With translation from Russian by Maksim Chernykh

Моя маленькая Антарктида (My Little Antarctica)

by Tatiana Frolova/KnAM Theater

Director: Tatiana Frolova

Premiered on 20 March 2020

Mit dem Aufruf des Videos erklären Sie sich einverstanden, dass Ihre Daten an YouTube übermittelt werden. Mehr dazu finden Sie in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

Bei Klick auf die Schaltfläche "Akzeptieren" wird ein Cookie auf Ihrem Computer abgelegt, so dass Sie für die Dauer einer Stunde, diese Meldung nicht mehr angezeigt bekommen.

Pearson’s Preview

Archive

April 2024

Icy Myths in the Russian East

The Exiles of KnAM’s »My Little Antarctica« at the Schaubühne

April 2023

FIND 2023

Nostalgic, Not Sentimental

The Wooster Group as »Artist in Focus« at the Schaubühne

| Page 1 of 10 pages |