FIND 2024

Reading Marx in a Tuscan Factory

Enrico Baraldi and Nicola Borghesi in conversation with Joseph Pearson

by Joseph Pearson

5 April 2024

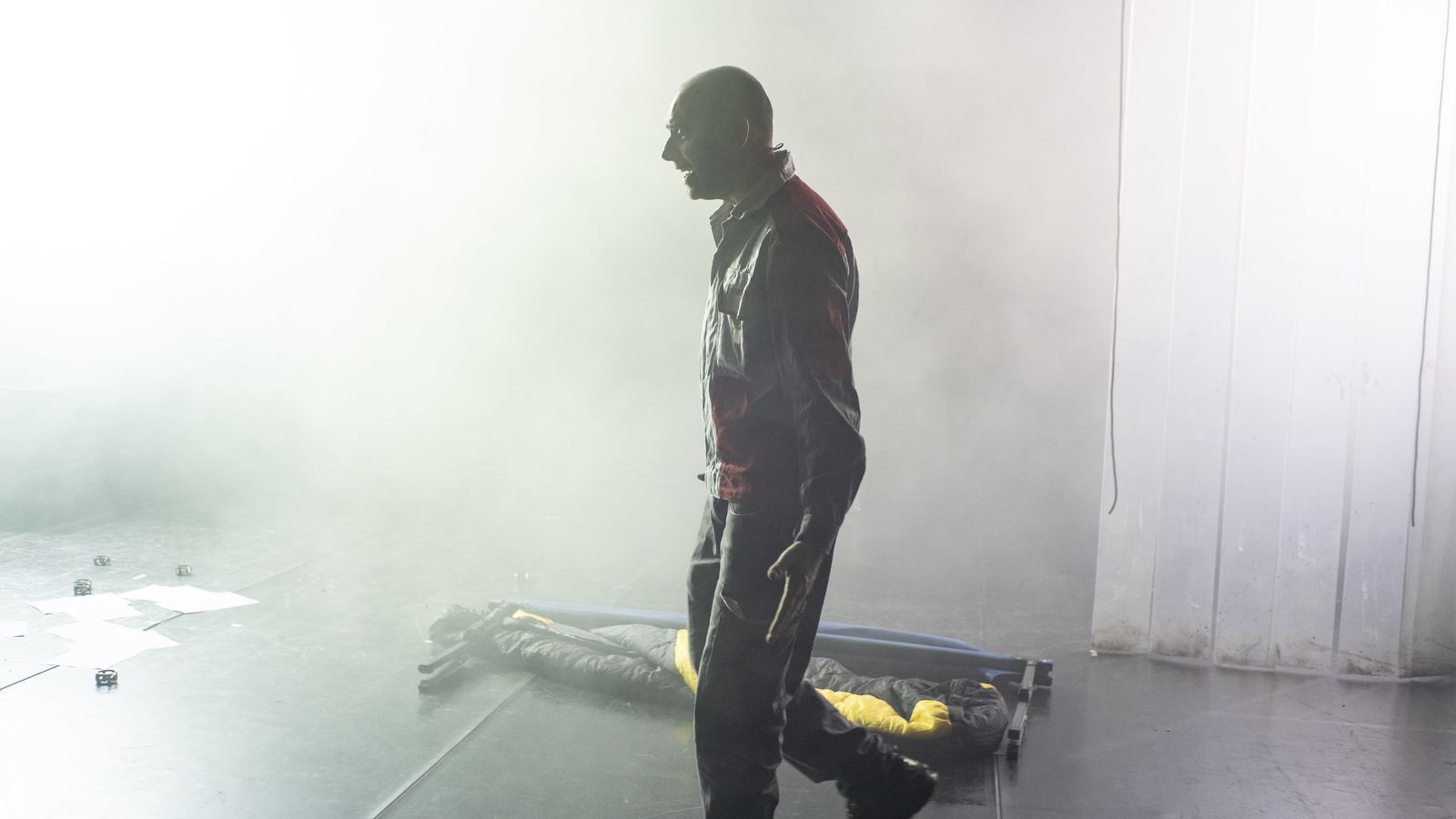

Just north of the Renaissance city of Florence is an industrial area. There, a GKN Driveline factory produced half-axles of cars, employing four hundred workers until one Saturday. On 9 July 2021, they were all put out of work––fired by email by the English investment firm Melrose, which had acquired the plant. Returning to their workplace, the workers busted open the front gate and ejected the bodyguards protecting the valuable machines. They have occupied the factory for over two and a half years. Their struggle is the subject of Kepler-452’s theatre piece, »Il Capitale – un libro che ancora non abbiamo letto« [Capital: A Book We’ve Not Yet Read], which appears at FIND 2024.

In Italy, the GKN occupation became a cause-célèbre. Central Italy is the historic heart of the Italian left and remains so even in a country now led by a neo-fascist party. As co-director Nicola Borghesi tells me from Bologna, »The workers’ movement has a specific story in Italy, where its fire was covered by the ashes of liberalism and the renunciation of a revolutionary, anti-capitalist role. Social-democratic movements often do well in moments of abundance of capital: the boss makes real money, and the worker gets a tip. But in the regions of Tuscany and Emilia Romagna there remains a strong ideal of redistribution. Under the rubble of the left still burns the embers of solidarity and a refusal to be dominated. There’s something profoundly Tuscan about not wanting to get fucked around«.

Here was a story of the means of production being seized by the working classes––it seemed a page (or many pages) taken from Marx’s volumes of Capital. Co-director Enrico Baraldi elaborates, »But what does it mean, in terms of Marx’s work, for a factory to be closed but still functional, and no longer producing capital? We thought this could be interesting, and so we went to a demo organised by the workers and left impressed. We felt their passion. This spark, heat, of human beings who had created an extended family in their protest seemed far from the coldness of Marx’s social-scientific text. We felt calore e freddo«.

It wasn’t long before the two directors moved into the factory with the workers, living among them, a copy of Marx’s Capital in hand. I asked them how the workers accepted them and Baraldi replies: »Because this occupation was an important phenomenon in Italy, many people were coming to the factory in solidarity. The workers were understandably cautious, worried about surveillance or someone coming at night and starting a fire, wrecking the occupation. We were among the many but didn’t appear to have a role to play. We told them, »We’re a theatre company, and we’d like to ask you some questions«, and they replied by giving us the nickname: »the policemen« because we were always going around, asking questions«.

Baraldi continues, »Nobody could understand what we were doing. It wasn’t clear to them we wanted to include workers in the production as non-professionals, or what we call »world actors«, »experts of everyday life«. It took them a while to understand it was possible to do this. We lived in the factory for a month and a half. We started out where the cars were kept. At a certain point, with time, we started to become friends and were promoted to an office, which was a little warmer. There were no showers, and it was winter«.

The directors tell me that collaborating with the workers was challenging. Borghesi describes them as »characterful, strong, moody, intense people«. Only through many late drinks and interviews did they begin to form a rapport.

»How then did you direct them? « I ask.

Borghesi replies, »Eventually, we invited them to the theatre. We sat in the first row and asked them to sit across––not quite on stage, but in the zone between the audience and the stage. We had them repeat their stories to us, without writing a fixed text. We only did this at the very end, but there was never a moment when we asked them to learn a text by memory–– that would be an error. Rather we worked with questions and invited them to be more and more detailed as they replied. Then we asked them to cut. From this we created blocks of story, or modules, that we could shape into a performance«.

»Do workers make good actors?« I ask.

Borghesi smiles, »At first, we were preoccupied that the workers might lose some spark in rehearsals, the spontaneity or emotive part of it, telling the same story repeatedly, but we soon realised: the worker is the person who is most used to repetitive action, and always the same action. We theorised this in the production and discovered that they could be even better than some professional actors«.

Industrial props appear on stage, and we speak about their role in the production, with Baraldi recounting: »There’s this scene where an actor-worker introduces himself and takes a half-axle, and says, »this is a half-axle«. We tried this scene with a piece of wood because we didn’t have a half-axle. But the scene never seemed to work. We asked him: why isn’t this working, Felice? But then, one day, we brought a half-axle on stage, and suddenly, the scene worked. As a worker, he couldn’t make-believe. We saw that some true objects can give reality to the story«.

»I’m thinking that this was all in the period following the Covid epidemic, which was particularly brutal in Italy. Did this impact your work in any way?« I ask.

Borghesi replies, »In the emergency, which was the pandemic, the state encroached profoundly on the liberty of individuals and companies. It asked people to stay at home. But Italy was also one of the few countries where it was illegal to fire a worker; work was guaranteed for a short time. And we thought: it’s not impossible for the state strongly to enter the economy and its social aspects. It happened in an emergency, which allowed people to accept it. But suddenly, how is it possible that we can wake up every morning and do what we want in a world where it is not possible to do what we want? We saw an entry to socialism: the state can choose production and the number of workers, going beyond individual liberty. And, of course, we liked this!«

»Leading you to Marx, and the GKN occupation––« I say, bringing us to the beginning of our conversation.

»We have always done political theatre, but we were its narrators or observers. In this way, I think the pandemic helped us. It made us understand as theatre-makers that we cannot simply recount. We need to take clear positions. We need to be part of a struggle«.

Interview in Italian. Translated by Joseph Pearson.

Il Capitale – un libro che ancora non abbiamo letto

by Kepler-452

Director: Kepler-452/Enrico Baraldi & Nicola Borghesi

Guest Performance FIND 2024

Bologna

Premiered on 20 April 2024

Mit dem Aufruf des Videos erklären Sie sich einverstanden, dass Ihre Daten an YouTube übermittelt werden. Mehr dazu finden Sie in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

Bei Klick auf die Schaltfläche "Akzeptieren" wird ein Cookie auf Ihrem Computer abgelegt, so dass Sie für die Dauer einer Stunde, diese Meldung nicht mehr angezeigt bekommen.

Pearson’s Preview

Archive

April 2024

Icy Myths in the Russian East

The Exiles of KnAM’s »My Little Antarctica« at the Schaubühne

April 2023

FIND 2023

Nostalgic, Not Sentimental

The Wooster Group as »Artist in Focus« at the Schaubühne

| Page 1 of 10 pages |