Love for Actors

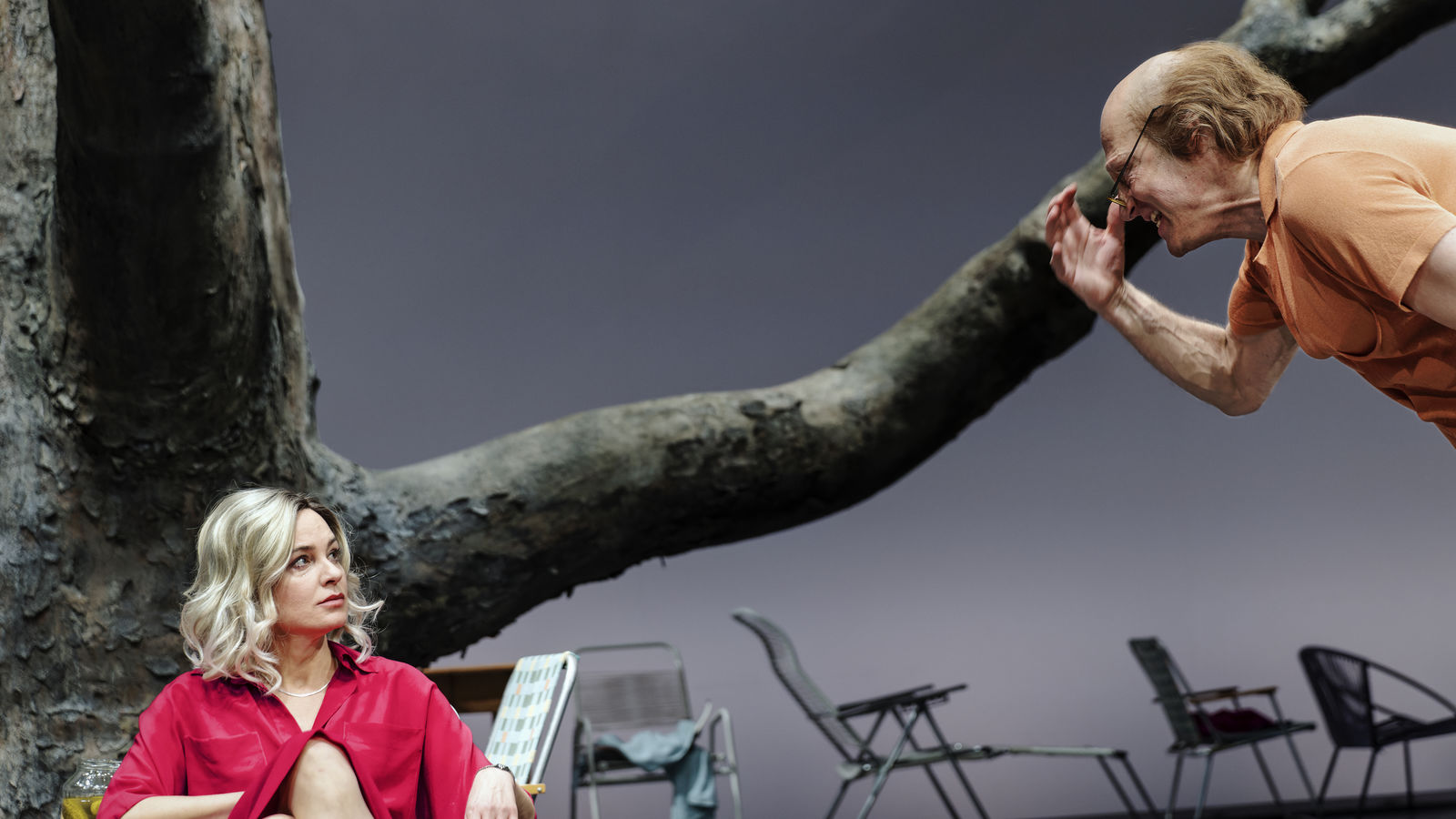

Thomas Ostermeier’s »The Seagull« at the Schaubühne

by Joseph Pearson

21 February 2023

Chekhov’s play about making plays lends itself to in-jokes. Consider casting Joachim Meyerhoff, a renowned writer, as Trigorin, a well-known writer. Or casting Laurenz Laufenberg, who writes the production’s play within the play, as Konstantin, or Kostja, a young man who writes a play within the play. Or casting Alina Vimbai Strähler, only a couple of years after she auditions for the Schaubühne ensemble with Nina’s speech from the final act––as Nina.

Anton Chekhov’s »The Seagull«, written in 1895, is set on a rural estate in Tsarist Russia. Young Kostja pens what he considers an innovative work, performed by Nina, a girl from the neighbouring estate, with whom he is infatuated. The play is rejected by his older audience, especially his mother, the ostentatious actress Arkadina (Stephanie Eidt), and the exploitative writer Trigorin. The result is crisis and tragedy. Chekhov was a sprightly 35 when he wrote »The Seagull«, and his Kostja champions »new forms« of theatre writing. Unsurprisingly, the play’s moral ambiguity––its eschewing of didactic writing and other 19th-century devices––confused »The Seagull’s« audience on opening night. It was a disastrous premiere.

While »The Seagull« is sometimes discussed as a play about conflicting generations of theatre makers, Ostermeier’s 2023 production at the Schaubühne endeavours to see the play through a different lens: by talking about love.

I meet the Schaubühne’s chief dramaturge, and playwright, Maja Zade, who tells me, »We are looking at love and variations of love, its different shades: such as whether we are first falling in love, whether it is unrequited or requited. We try to be precise about those differences. There is a deliberate decision to focus on love and on the actors. We are doing actors and text. People doing scenes together«.

The characters of Chekhov’s play usually look for love where it is denied, and then reject it when it is offered to them. Zade points to the primary example: the relationship between the aspiring Kostja and his established and famous mother, Arkadina.

»I think Kostja’s relationship with Arkadina is central: wanting love from his mother and never entirely getting it. She was a working mother and not always there, one assumes. And we also assume that is why his need to be loved is expressed with the feelings of a little child, with his fits of jealousy towards Trigorin. Not just because Trigorin is taking the mother away but also because the terrible thing happens that Trigorin also falls in love with Nina. Kostja’s love for Nina is also linked to his artistic aspirations. She is an actress fulfilling his creative dream. In the end, Kostja is desperate because of these two things: his mother doesn’t respect him as an artist, and Nina remains in love with Trigorin and still has the hope to make it as an actor, while Kostja has lost his dreams. He realises he will not get love on a private level or as a successful artist, and these two things break him. But these are connected: you can see how these characters make art to be loved«.

I reply, »Let’s return to that moment early in the play when Kostja reaches out to his mother with his artwork, a play that he performs for the other actors in the first act. I don’t feel like Chekhov is mocking Kostja. But there is also the sense that as an artist, Kostja is still green and needs to develop his potential. Chekhov makes Kostja’s play symbolist, but that idiom would hardly be challenging in a production set in 2023. How does your play tackle this problem?«

Zade replies, »It’s quite tricky, the theatre thing. You want to make it contemporary, but today’s conflict isn’t about symbolism or naturalism. You want to be subtle about it but not too obvious. Laurenz, in fact, took up this challenge and wrote the play himself, rehearsing a lot of it independently with Alina.«.

»I heard that, more generally, a lot of freedom has been given to the actors in this production in developing their lines, in something of a devised departure from Regietheatre«, I reply.

»Yes, there’s been an adapting and rewriting process that we’ve never done before. Usually, we prepare a version in advance and go to rehearsals with it. But here, the actors have rephrased their texts, with the task to remain close to the original but with the freedom to make it more personal. I’ve been interested to see how the actors have responded: some have only changed one or two words, while others have really gone for it. It brings with it a sense of ownership of the play. You also really need to talk to the other actors if you change something, because it can quickly change what the scene is about«.

I reply, »It must be time-consuming as the dramaturge on the production––«

Zade replies, »Yes, more than usual. We initially thought the script would be done in two weeks, but it took much longer. The actors often need to try things out on stage instead of on paper. Meanwhile, I’m literally sitting with two versions––the Chekhov translation and our version–– keeping track whether the words stray too far from the original. For Thomas [Ostermeier], it’s a very relaxed and generous way for him to direct––to say: the text is also your responsibility«.

We talk more about the technical aspects of the production. Ostermeier has directed »The Seagull« before, in Amsterdam (2013) and Lausanne in 2016. But this iteration is completely new, including the set, which involves a new seating configuration in Saal B, where half the auditorium is blocked off, and the audience is sitting on stage, in the round. An enormous tree dominates the scene and rises over the audience. The effect is very intimate.

»You are incredibly close to the actors, which also brings about challenges in terms of acting. Everything must be so much more precise and small, to the extent that it doesn’t seem theatrical«, says Zade.

»What I like about Chekhov is the enormously intimate worlds that his characters create with only a few lines––« I say.

»Yes, we’ve talked a lot about the scenes being impressionistic. There is a little dot of colour here, but an iceberg underneath. A tiny moment, a tiny scene that passes quickly, but so much behind it«.

She continues, »I think »The Seagull« is his best play. It’s because it’s more tightly knit than the others. A lot happening, more action packed. It’s amazing every single character has this huge amount of background. Even smaller characters seem completely realised. We realised this once we started rephrasing it. As soon as you start adding, the rhythm falls apart, and you realise how good it is: its rhythm and pace. I think we’ve literally made no cuts––which you would normally do––because you lose things. It’s quite short because it’s quite fast; there’s no need to get rid of anything. It's a cliché that every director who does the play says it’s a comedy. But when I’ve seen it has not been. In our version, it’s very funny. That’s the brilliance: it’s desperately sad but also so funny. You recognise yourself and see how the pain and the comedy intertwine«.

However beautifully crafted, any play written in 1895 but set today might suffer from the transposition, and my final question to Maja Zade is how »The Seagull« looks through a feminist lens.

Zade replies, »It’s surprisingly contemporary. It is one of the few plays of that age where I think: women are still like that today. What’s often forgotten in productions is that the play contains two women artists, Nina and Arkadina, who have professions. And you think that the lives of the other women, who do not, would have been happier if they had another outlet. A job or a calling. I think it’s up to interpretation, but I think that especially Nina and Arkadina are strong characters, that they are fighters, despite everything that happens to Nina. On some level, she is broken in the fourth act, but she leaves saying: I will make it as an artist. I will find success. I envision this future for her, that she will find her way––«.

Die Möwe (The Seagull)

by Anton Chekhov

In a version by the ensemble using the translation by Ulrike Zemme

Director: Thomas Ostermeier

Premiered on 7 March 2023

Mit dem Aufruf des Videos erklären Sie sich einverstanden, dass Ihre Daten an YouTube übermittelt werden. Mehr dazu finden Sie in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

Bei Klick auf die Schaltfläche "Akzeptieren" wird ein Cookie auf Ihrem Computer abgelegt, so dass Sie für die Dauer einer Stunde, diese Meldung nicht mehr angezeigt bekommen.

Pearson’s Preview

Archive

January 2015

Celebrating Evil: Richard III at the Schaubühne

December 2014

An Autopsy of the GDR: Armin Petras’ Divided Heaven

| Page 9 of 10 pages |