FIND 2024

»I Am Not One of These People«

Martin Crimp and Christian Lapointe in Conversation with Joseph Pearson

by Joseph Pearson

12 April 2024

The title, »Not One of These People« already gives a clue to how playwright/performer Martin Crimp and director Christian Lapointe of Québec’s Carte Blanche tackle questions of authorship, fiction, embodiment, and responsibility on stage.

Crimp has for some time been a household name in the London theatre scene, well-known for his plays »The rest will be familiar to you from cinema« (2013) and »Attempts on her Life« (1997). Here we find him in fruitful collaboration with Lapointe, recognised not only for having participated in the Avignon Festival and his stagings of symbolist plays (such as those based on Maeterlinck or Yeats), but also for work that verges on performance art (such as 70-hour durational pieces on Artaud).

Like in many performances in this year’s FIND festival at the Schaubühne, the imprint of the Covid pandemic is present, both in terms of the play’s structure and how it was made. Already, using Zoom to interview Crimp in the UK and Lapointe in Québec reminds me of those years and the weirdness of how friends and family appeared disembodied, almost computer-generated, by a technology that kept us together.

Since the performance space could not be packed under Covid restrictions, Crimp’s original idea was to »pandemic-enable« his work so that the audience could come and go, experiencing it in parts. »Not One of These People« was to be five hours long, with 1000 different voices, inspired, in part, by Forced Entertainment’s durational piece »Speak Bitterness« (1994), in which six actors read a series of confessions from a long table over six hours. However, these plans changed, and Crimp tells me, »When I got to 299 voices, I thought I’d stop there. The first hundred are about what I call cultural toothache, the second hundred are confessions––in homage to Forced Entertainment––and then the last 99 are predicated on chance«.

Crimp wrote the play in lockdown and tells me how he took great pleasure in sharing his work in stages with his wife and daughter (»I tell young writers, if you are not experiencing pleasure while writing, no one will do so reading it!«). The creating and imparting of stories in a closed environment, with a pandemic raging outside the door, has its Boccaccio-esque parallels, and Crimp explains how he »absorbed this quality subliminally. I knew I wanted a very formal text, in the way that the Decameron has a map decided in advance. But the final formal structure of what we see on stage, which was developed by Christian, with a bit of input from me, cuts across and subverts my original boundaries«.

Lapointe was challenged to cast a play with 299 different personalities, and he found a novel solution, one that gets to the heart of many of theatre’s big questions about inventing character. Hundreds of projected individuals––all of them deep fakes––would be created by artificial intelligence.

Lapointe speaks to me about his process: »The website, »This Person Does Not Exist«, which generates faces of fake people, was the right place for our casting because Martin had invented people, like he does in all his plays––and like most traditional drama. And at the same time, it’s funny how we’re getting close to the »super marionette« of [Edward Gordon] Craig« ––the puppet that replaces the actor.

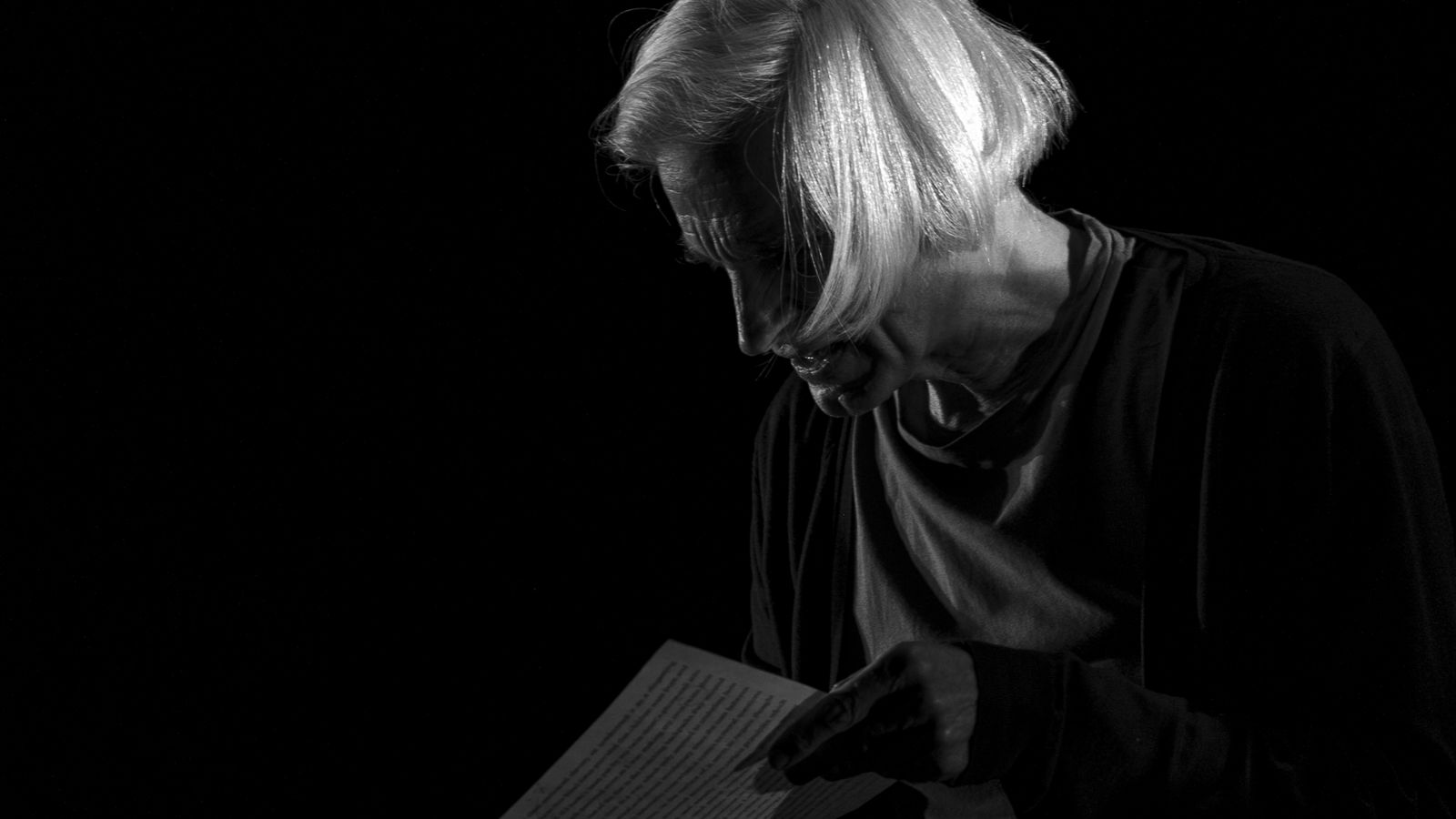

Only Crimp appears as an embodied performer on stage, where he provides his own voice to each one of these disembodied projections. He tells me about his experience of being thrust into the spotlight, »In British culture, the author never appears on stage, not even at a premiere. So, when I found myself being a performer, the first thing I noticed was the intense awareness of the body, the dryness of the throat, the feeling in the stomach before going on stage. The main lesson from this connection to my own body on-stage was: while the writer can be disembodied, the performer has to be embodied«.

In this case, however, the playwright is not only present but also speaks the words of his invented characters. Crimp explains this phenomenon much better than I can: »What happens in this play, it seems to me, is very close to the process of any play, putting bodies on-stage which are not the author’s body. I would return to the fact that this is what the playwright always does: other people will always embody what is written, and this piece lays bare that process, since the illusion is taken away by Christian’s concept for the performance. I would imagine if we cast the piece with real actors, we would obviously do it with people who are in a position to say those things. But then we might ask, must an actor share a character’s biography?«

Indeed, much of the press reception of this play has been about what Lapointe tells me is the problem of »who writes what for whom«. He explains, »When reading the play’s text, one can deduce partially who might say what. This is a female, this is a male, this is a black woman, this is a queer man, this is a trans woman. But the question raised by the casting is political: who embodies the characters?«.

(As a festival viewing tip, I would suggest––if you would like to enter an exciting argumentative dialectic––discussing this play in parallel with Renata Carvalho’s »Manifesto Transpofágico«, an activist cry for the importance of putting embodied trans voices on stage).

Lapointe continues by explaining that when they began to develop the play at the Royal Court Theatre in London, initially it was »unclear if the faces would be randomly generated every night. The political responsibility of who speaks these lines would then have been absolved by the machine. But definitively casting all these people ourselves was a tough but necessary part of the process because »who speaks« is the political question, somehow«.

I ask Lapointe to elaborate and he tells me, »We’ve seen this question in criticism of Robert Lepage’s work. You can take, for example, the culture of Bavarians––who have for a very long time had the money, the exposure, and the mechanism available to tell their own stories––and put it on stage, but to take the stories of indigenous Canadians who historically have not had the representation and money to put their own story on stage raises an important question of distributive justice, of which »appropriation« is a symptom. We’ve been thoughtful about which pictures should be affiliated with which line, because I believe the casting is a big part of the dramaturgy and the storytelling«.

Crimp continues, »My job as a performer is to stay in the zone where Christian wants me to be. It’s not the »voix blanche« of the writer. Because, for me, my voice is always emotionally committed to the characters I invent. One thing I learned as I wrote is that whereas I was initially reacting to the question »who can say what«, which differs from culture to culture, I was, in the end, exploring the limits of my imagination. At times, very reactionary voices emerge. One of the characters in the play says, »I’ll write what the fuck I like«. But of course, that’s just bravado. We all have limits. And for a writer those limits are the limits of his or her imagined world«.

Christian Lapointe elucidates, »When that character says, »I’ll write what the fuck I like«, let’s be clear that it’s not Martin Crimp saying that. The play is a lot about: none of these people exist, and none of these people are Martin Crimp. Where the tension is, and what links them, is that they are all invented by someone they are not, and they are not outside of this invention. I think this tension dramaturgically holds the play together«.

Martin Crimp replies, »Thank you for saying that, Christian. The title is »Not One of These People«. I invented all these people, meaning that I am none of them, but at the same time all of them. This is the paradox of every playwright«.

____

* Conversation partly in French, translations to English by Joseph Pearson

Not One of These People

by Martin Crimp

Director: Christian Lapointe

Premiered on 23 April 2024

Mit dem Aufruf des Videos erklären Sie sich einverstanden, dass Ihre Daten an YouTube übermittelt werden. Mehr dazu finden Sie in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

Bei Klick auf die Schaltfläche "Akzeptieren" wird ein Cookie auf Ihrem Computer abgelegt, so dass Sie für die Dauer einer Stunde, diese Meldung nicht mehr angezeigt bekommen.

Pearson’s Preview

Archive

April 2024

Icy Myths in the Russian East

The Exiles of KnAM’s »My Little Antarctica« at the Schaubühne

April 2023

FIND 2023

Nostalgic, Not Sentimental

The Wooster Group as »Artist in Focus« at the Schaubühne

| Page 1 of 10 pages |