Rockers, Balzac, and Neoliberalism: »Vernon Subutex 1« at the Schaubühne

By Joseph Pearson

22 October 2020

For once, I visit a rehearsal at the Schaubühne, not at the practice stage in Reinickendorf but the main venue on Kurfürstendamm. The theatre, after all, has been emptied of performances for months with the ongoing Coronavirus epidemic. The café is full of protective plastic partitions and rehearsals depend on a regime of regular testing and designated officers who enforce distancing.

Thomas Ostermeier’s newest creation, »Vernon Subutex I«, based on the novel by Virginie Despentes, is a testament of endurance. It was originally scheduled to premiere in May 2020. Now we find ourselves in October with the premiere planned for November. Even this date isn’t guaranteed. Still, everyone continues with the work.

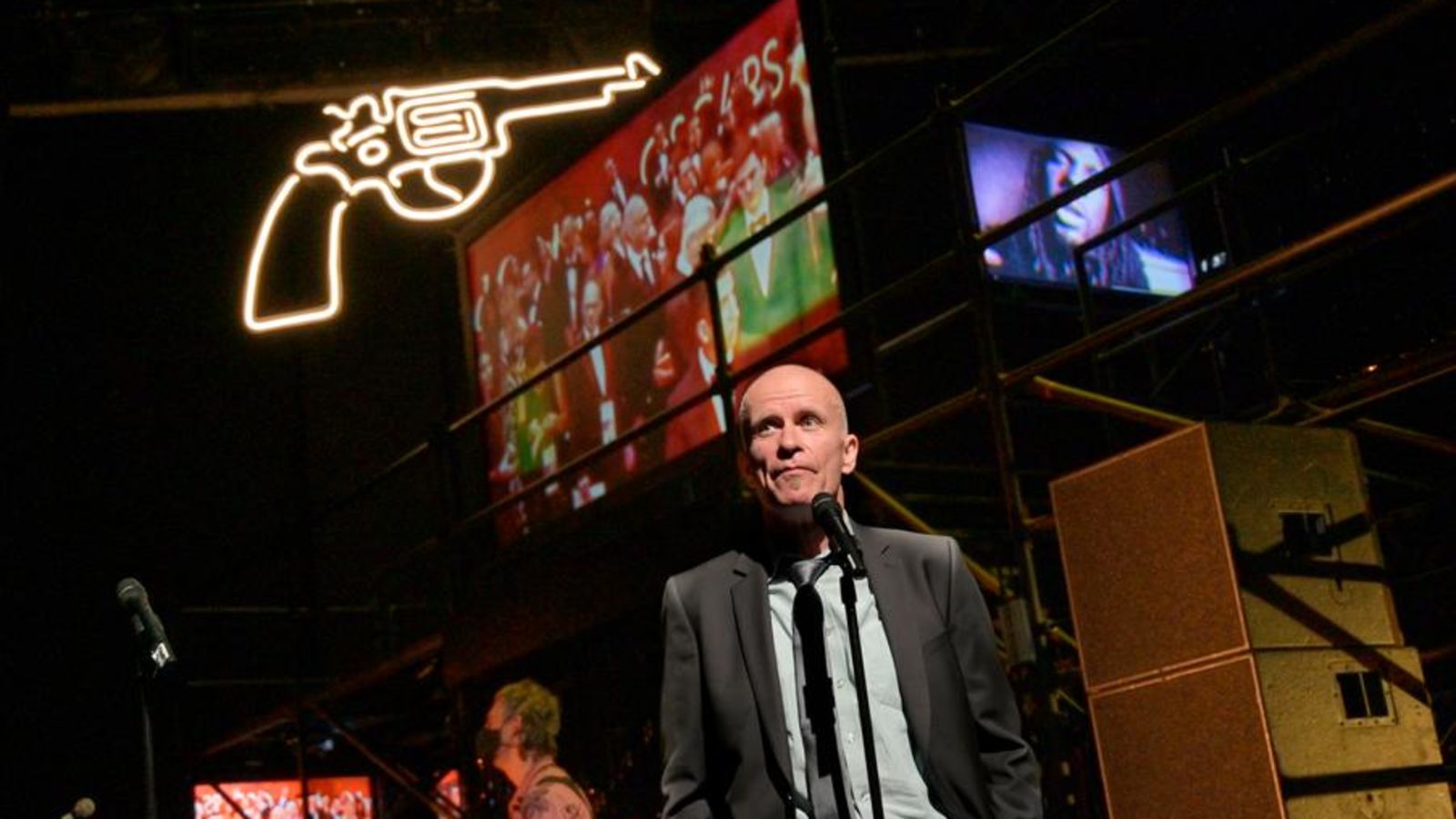

I have spent many months outside the theatre. So, when I enter Saal A, the sudden sight of the modular set, revolving like an LP under the atmospheric lights, stirs up strong feelings. It’s a social world off-limits to most of us right now. Live music! A rock band! Ruth Rosenfeld sings Sonic Youth’s »Bull in the Heather«, her hands fluttering around her swaying body, in a field of chrome, pleather, black piping, and tube lighting. A gun hangs over the rocker scene like a portent. The entire spectacle, with its scaffolding of video, appears as an enormous installation.

Thomas Ostermeier tells me that he wanted to reproduce the spirit of a rock concert.

»The set is like bar or club in Kreuzberg where I’d feel comfortable, a run-down apartment, an old record shop, the feeling of that world we knew when we were 20 but is now gone. What has become of rock and roll culture? To punk and our ideals of anarchy and changing the world?«

While Berlin might be a little behind Paris in the corporate take-over, the protagonist’s story of becoming homeless after he loses his record store will resonate.

»Berliners know the spirit of SO36 and squatting houses. People from any city will recognise what happens when you made your living as a bass guitar player in any modest punk band and didn’t become famous. You can’t become a rock and roll star at 50. And now your apartment is being pulled from under your feet«.

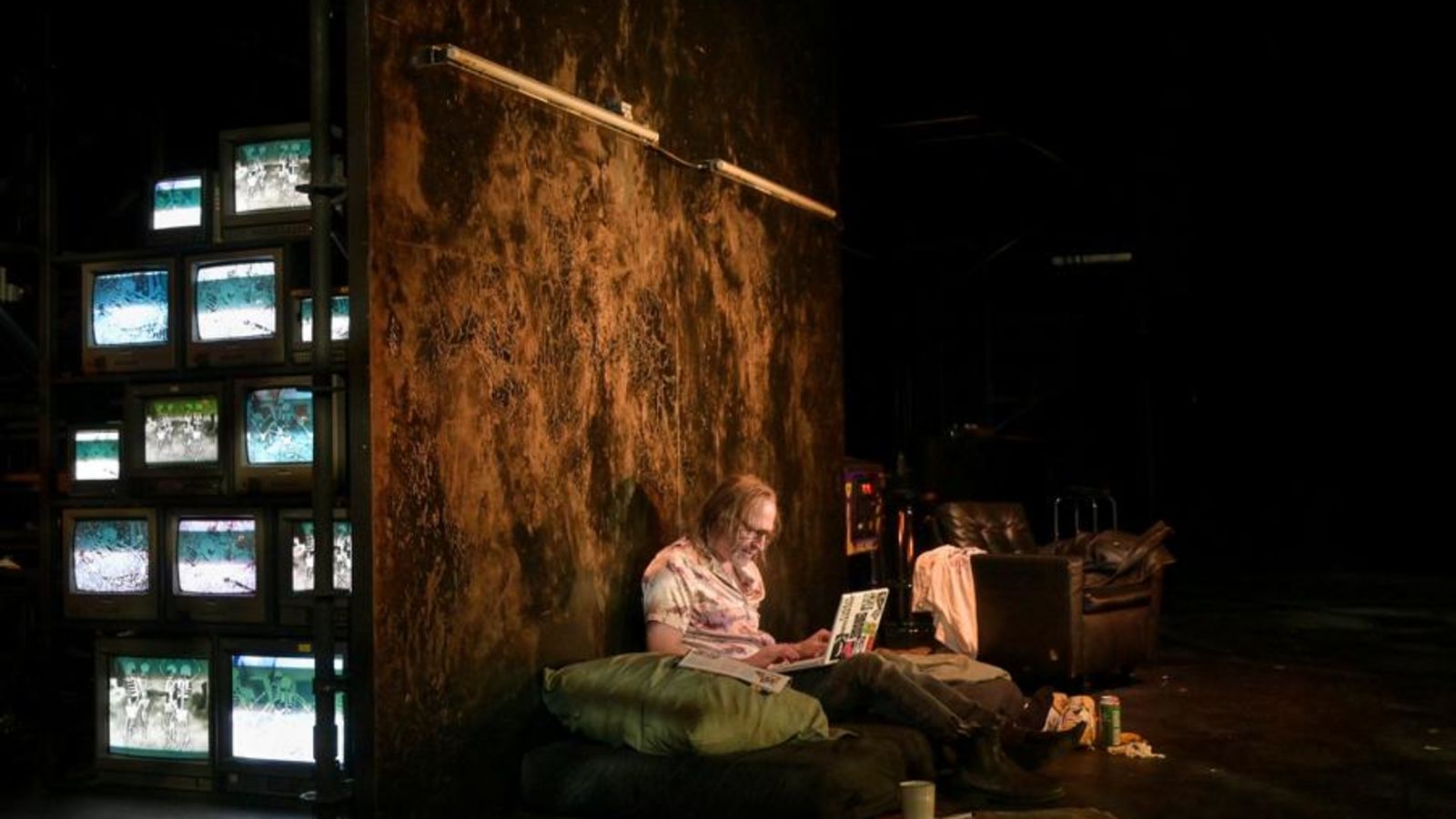

The atmospheric world on-stage is threatened by the market and financial crises. Video projections afford us glimpses to the underbelly of Paris: homeless people, discounter shops, an elderly man feeding pigeons from his grocery cart. The Coronavirus crisis has only exacerbated this older problem of income inequality, accelerating the closure of so many of these rocker venues.

Ostermeier tells me, »With COVID, many musicians are in trouble. Virginie Despentes feels that COVID produces more Vernons––more victims«.

The volume of the band on-stage grows. Henri Jakobs rocks his bass. Ten, twenty, thirty, forty /Tell me that you want to scold me / Tell me that you a-dore me / Tell me that you're famous for me. A video funnels us into the underpass of a Parisian freeway. The image of a woman absorbed on her mobile phone flickers on the scene. We have the feeling of rushing forward as the set revolves.

Ostermeier follows my attention, »We didn’t pick the obvious rock hits. Not ones you recognise at once. We went for some pearls of rock history: Dead Kennedys, Gang of Four. Maybe the whole production will only be understood by people who share this musical taste, who have been in leftist radical circles, squatted houses, been part of »Gegenkultur« phenomenon. It’s an evening for connoisseurs«.

Virginie Despentes’s novel »Vernon Subutex I«, was published on the morning of the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks. She has a habit of anticipating social tension: her novel and film, »Rape Me« (»Baise-Moi«, 1994/2000), and essay »King Kong Theory« hailed a French neo-feminism. These works celebrated an aggressive feminine sexuality that challenged received feminist objections to pornography and prostitution. Despentes’s series of three »Vernon Subutex« novels (2015-2017) steer away from explicit sexuality. Instead, the crisis of a generation––Generation X-ers in their fifties, grappling with the alienations of neoliberalism, political extremism, right-wing violence, and jihadism––is in her sights.

The vehicle for critique is a »has-been«: Vernon, last name Subutex (suggesting, like a clever line of a French chanson, both the heroin treatment and an invitation to close reading). After the failure of his record store, Subutex is homeless. »La crise du disque« is just one symbol for the crisis of automation and technological unemployment explored in the book. Subutex is forced to catch up with old friends and enemies so he can couch-surf. The itinerant bed-hopper is a Fabian: wandering Paris, destitute, into the lives of these former 90s-band groupies who have grown up to become neoliberal subjects, obsessed with fame, money, self-gratification. They are victims of all of the above.

Despentes’s writings can make you furious. Her language is crude; she doesn’t censor her characters’ racist and sexist idiom. Name-dropping––of defunct bands, the names of clubs and apps––is a constant pitter-patter. It is the ephemeral junk of pop culture, the kind you might have heard over the plasticised LPs of Vernon’s record shop before it went bust. The perambulating author omnisciently inhabits various narrators on the coattails of homeless Vernon. The focalised narration is either a guilty pleasure––or ugly voyeurism––depending on your impression of the ensuing »bitch-fest« (her language). Hiding in the centre of this trash heap (I imagine someone in pearls and stilettos excavating at the dumpster) is the void left by a recently deceased rock star, Alex Bleach.

»Vernon Subutex« is not intended to make the reader comfortable. Despentes’s garbage is carefully organised and we are looking for something in it. Everyone is after the acrid scent of the deceased famous person, his eponymous but corrosive cleansing power. The void of his death stands in for the lost dreams of a generation.

The packaging of the novel is its critique of neoliberalism and Despentes’s portraits are lessons in failure. You don’t need to dig deep to unearth her syndicalist upbringing: her solidarity with not only the poor but also–– intersectionally––the socially marginal, such as immigrants and trans people. »Vernon Subutex« is a dirge for a generation but also a cry of pain for the future, in which young people can no longer be counted on to be good lefties. Surprisingly, it is also a testament to the accidental solidarity, and knack for survival, of those who have otherwise been stripped of everything.

A frequent visitor to the Schaubühne will notice that Ostermeier productions of late – »Returning to Reims, »A History of Violence«, »Youth without God« – have been prose adaptations.

»That many are French is an accident«, he tells me, »And one doesn’t necessarily lead into the other: nothing I learned from »Histoire de la violence« prepared me for »Vernon Subutex«. The novel’s structure was theatrical, because of the constantly changing point of view. But the challenge was to put a series of monologues on stage in a way that was not static. You will notice that one-third of the evening is music, which is very important«.

I am about to ask: Why did you choose a book that is so difficult to put on stage?

But I remember Thomas once told me: »I like difficult!«

I ask instead: Why did you choose »Vernon Subutex«?

»Because of the novel’s construction, of someone who ends up without an apartment. Virginie Despentes gives this protagonist the possibility to meet different milieus, different places and people. With this construction, she makes possible a Balzac-like societal panorama. Any filmmaker or novelist dreams of one day being able to tell it all, the stories that connect individuals to get to a bigger view of contemporary society. That is what »Vernon Subutex« tries to do, incredibly beautifully, and with feminist and trans perspectives that are rare.«

»I also thought of Balzac«, I tell him, »Vernon shows us how friends and old acquaintances instrumentalise each other. Friendship is a form of social manoeuvring. It’s a familiar trope about Paris«

»Yes, but not just Paris. Vernon wanders at the edges of a world of pop culture, glamour, and social media, which the audience will recognise. It is a world which pretends that anyone who fights hard enough can make it and can even make money out of it. Which is a lie. For our generation, there was still this promise that we might build up a more equal world. Instead today things are less social and more unjust.«

Vernon Subutex 1

by Virginie Despentes

In a version by Florian Borchmeyer, Bettina Ehrlich and Thomas Ostermeier

Translated from French by Claudia Steinitz

Director: Thomas Ostermeier

Premiered on 4 June 2021

Mit dem Aufruf des Videos erklären Sie sich einverstanden, dass Ihre Daten an YouTube übermittelt werden. Mehr dazu finden Sie in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

Bei Klick auf die Schaltfläche "Akzeptieren" wird ein Cookie auf Ihrem Computer abgelegt, so dass Sie für die Dauer einer Stunde, diese Meldung nicht mehr angezeigt bekommen.

Pearson’s Preview

Archive

September 2021

Two Absent Artists at the Schaubühne

An Interview with Kirill Serebrennikov about »Outside«

August 2021

Oedipus, but not a Rewriting

November 2020

A Reply to Distancing, with »Michael Kohlhaas«

February 2020

The Missing Link in Marius von Mayenburg’s »The Apes«

October 2019

Playing Lego with Herbert Fritsch

| Page 3 of 10 pages |