Playing with Change Lars Eidinger and John Bock’s Collaborative Peer Gynt

By Joseph Pearson

28 January 2020

»Peer Gynt«, premiering at the Schaubühne this February, is something of an event as it brings together the talents of the actor Lars Eidinger and the artist John Bock.

Let me begin with Eidinger since––on the way to rehearsal, musing on the U-Bahn––I asked myself what kind of play might appeal to him as a director and actor? Somewhere between Rosenthaler Platz and Paracelsus Bad stations, I came up with a list of criteria (just guesses): 1.) must have a hero with the capacity for psychological depth: this is the man, after all, who embodied Hamlet and Richard III; 2.) must be wild and fantastical: one begins to admire the capacity for playfulness in Eidinger’s work having seen Rodrigo Garcia’s »I’d Rather Goya Robbed Me of Sleep than Some Arsehole« or Thomas Ostermeier’s »A Midsummer’s Night Dream«; 3.) must have the capacity to push boundaries: Eidinger is famously unafraid of a shitstorm.

Peer Gynt checks all these boxes. Ibsen wrote of his 1867 play in verse that it was »reckless and formless, written with no thought of the consequences«. It could not even be created at home––only abroad, on a Southern Italian journey. Peer Gynt has the imprint of the itinerant––picaresque and episodic in character, spread over continents––with enough distance from the Heimat to imbue the work with a hefty dose of satire. Not only are Romantic and individualistic strains of the Norwegian temperament picked apart, so too is a national mythology peopled with trolls and milkmaids. As the play sprawls geographically, with its large cast of characters that spring from Peer Gynt’s imagination, it blurs fantasy and reality. But it is the protagonist, a fortune-seeking Norwegian peasant, who ties the novel together. In the vein of a negative Bildungsroman, Peer Gynt goes abroad for self-realization but returns home a broken man.

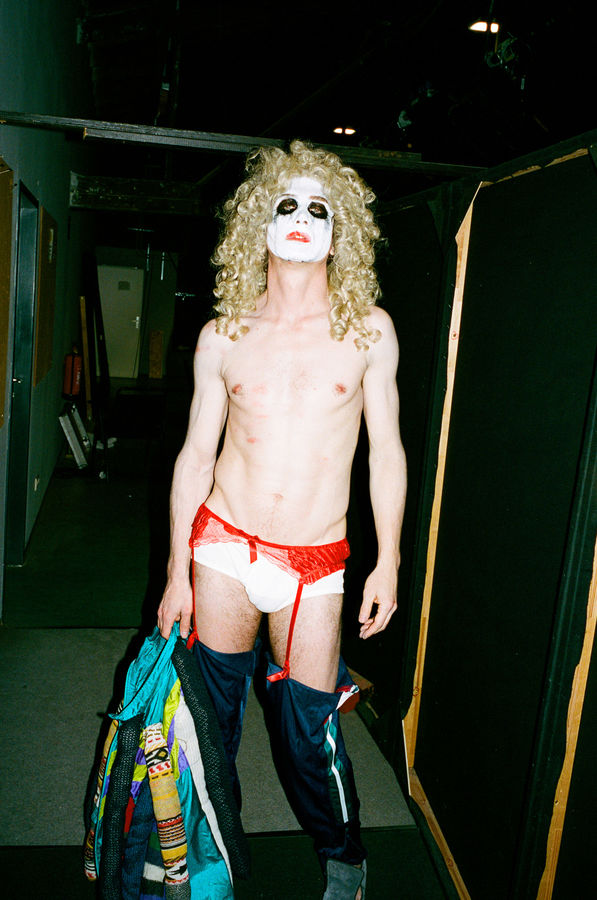

I arrive at the Schaubühne’s practice stage to discover a sprawling modular set: of tents and restricted spaces, slides, places for crawling around. It seems a space for improvisation and self-discovery––for being animal-like, for blurring fantasy and reality. From a corner, I hear the synthpop strains of A-ha. There’s an enormous screen: on which passes the random, identity-splicing aesthetic of internet video consumption. Eidinger arrives in tight underwear and garters, a blond wig, a white face of make-up. He also wears, improbably, a plush green toilet seat on his head. (And am I the only one who has noticed how much Lars eats on stage?) The scene in the hall of the Troll King that follows pulses with the eclectic, shimmering, and wild.

At first, the set appears a massive playpen or playground for Eidinger as the sole actor of the production––after all, I heard the phrase »baby punk« bandied around the set––but John Bock, who made the stage design and costumes, swiftly corrects me that it’s not a playground at all. The set has rather the feeling of a barn, an agricultural flavour. You’ll have to see! But the work is, at least to my eye, identifiably Bock: the multi-level constructions, collage of everyday objects, mix of video and performance. It’s a remarkable spatial installation touched by the grotesque.

What I see in common between Eidinger and Bock is this streak of whimsy. I ask how they came to work together.

»We work very well together«, says Bock, »One has an idea, the other one assembles it, one cuts something away, another one pastes something new inside. It’s like playing with change. And it works very well«.

»I was one of John’s fans for a long time«, says Lars.

»I had no idea!« says Bock.

Eidinger describes seeing one of his exhibits in Switzerland. And then an installation at an art fair in Berlin, where he was drawing on paper plates on which he served Toast Hawaii (for the non-initiated: an open-faced ham and cheese sandwich, grilled and adorned with a maraschino cherry on a pineapple ring).

»Everyone was so excited, they wanted their own little artwork by John«, says Eidinger.

»And the toast too, I imagine.«, I add.

»Yes, they were hot for the toast! I was waiting for one and John said: here’s one for someone who eats dirt so beautifully! And I understood then that he had seen Hamlet. He gave me his number and he started coming to the theatre. We started doing performances together, and two films. That is how we met. I always wanted to play Peer Gynt, the way I have always wanted to do Hamlet and Richard, and so I asked John if he could imagine doing theatre. He was immediately interested. He didn’t have to think about it: he immediately said yes«.

Then, what of Peer Gynt as a protagonist? Is he an anti-hero, a poet, a free spirit, or just lying and feckless? I turn to Eidinger and ask, ‘Do you like Peer Gynt as a character?’

»I try to play roles with which I can identify, but I am not interested in judging. I think instead: where is the starting point with this character? How can I make the most of him, as I have tried with Hamlet or Richard? But yes, I like him«.

Eidinger goes on to discuss the dreamlike quality of the piece, »The figures that Peer Gynt confronts spring from his fantasy. Each one of them has something of him: part of his personality. Solveig, for example, I see as the childlike self of Peer Gynt, something imprinted on him that through his travels and traumas has been locked away inside of himself«.

»Is Peer Gynt an anti-hero?« I ask.

»None of us are heroes. The hero is fictitious, an invention, it’s a romantic idea and is not realisable. We are all anti-heroes. The hope is that the public will look at Peer Gynt and recognise themselves. Because while one might strive to be a hero, with the anti-hero one is brought to reflection«.

Listening to Eidinger speak about these question of identity, I ask if they have chosen to focus on the more intimate and psychological possibilities of Ibsen’s play rather than its political satire and social critique.

John Bock replies, »There is this demand that one must react politically and make a statement for the seated audience. But these concerns are far from ours. We offer a subjective view, which we throw at the feet of the public, and whether they like it or not, they are free to decide. We do not wish to educate the public morally. Would you agree, Lars?«

Lars laughs, »Yes, except, it does matter to me if they like it or not! I want them to like it very much!«

Peer Gynt

by Henrik Ibsen

A Main-Brain-Drain-Drama by John Bock and Lars Eidinger

Premiered on 12 February 2020

Mit dem Aufruf des Videos erklären Sie sich einverstanden, dass Ihre Daten an YouTube übermittelt werden. Mehr dazu finden Sie in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

Bei Klick auf die Schaltfläche "Akzeptieren" wird ein Cookie auf Ihrem Computer abgelegt, so dass Sie für die Dauer einer Stunde, diese Meldung nicht mehr angezeigt bekommen.

Pearson’s Preview

Archive

April 2024

Icy Myths in the Russian East

The Exiles of KnAM’s »My Little Antarctica« at the Schaubühne

April 2023

FIND 2023

Nostalgic, Not Sentimental

The Wooster Group as »Artist in Focus« at the Schaubühne

| Page 1 of 10 pages |